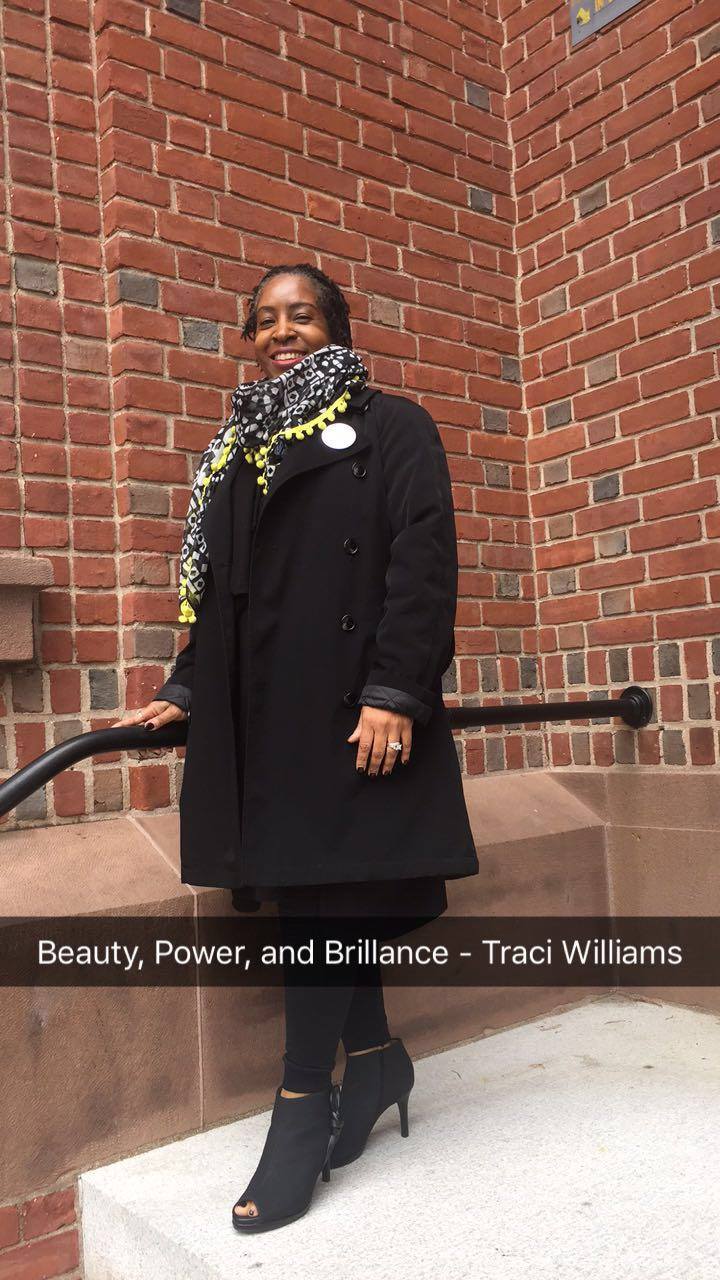

A Conversation with Traci Williams, AC '18J

Interviewed by Cressida Roe ‘21

What inspired you to start writing in the very beginning?

It’s my voice. It’s the way I started to speak. I grew up in a household where children were seen and not heard. I would write down the things I wanted to say, and so I wouldn’t get caught, I wrote them as “stories.” I’m right-handed, but I would write with my left hand, so my handwriting wouldn’t be recognized. It began when I was five or six years old.

How do you find your life and personal story reflected in your art?

I would say everywhere. It’s fiction but its historical fiction. Everything I write is based around true events. In the Four Plays [which are being read at the Hallie Flanagan Theater at the end of November], each play is woven around events that have occurred in my life. Either directly or indirectly, everything that comes out has happened.

In the poem by Otelia Cromwell, she says: the genius does not write to please. Otelia Cromwell’s words resonate with me. I write for myself, not an audience. I told you about this fear of being caught. And if it’s healing, why should I care? Why should I try to please someone else?

What’s going to be interesting for me is to be in the audience and hear these readings of my plays. I don’t know that I’ve shared all of them, except with my professor, who has seen them, but many people have not. Reading my things in print is one thing, but to have the characters actually come to life from the page…it’s going to be much different.

How has Smith impacted you as a writer?

Smith has me writing about things that I didn’t know I would ever write about—has me thinking and caring about new things. For example, one of the plays that I wrote, BOXES. When I initially began writing, it was about color, a person who passes as white. And this character morphed into an androgynous character. When I talked to someone about it, I was like, “I don’t know what’s going on,” but I followed the character. These were about things I didn’t think I thought affected me. So Smith has allowed me to see things other than my little black southern world. And Smith has given me the freedom to write it.

Though I’m an Africana Studies Major, all I wanted to do was write. I had a Community College associates degree in English and African-American literature, but I wanted to write. Here, they helped me pick courses that would give me the freedom to write. It’s paying off. Well, I’ll say it pays off when it “pays” off, but right now, I’m enjoying the freedom and the liberty to do it.

This poem you have is filed under “Inked at Smith,” where I keep all I did during the five and a half semesters I was here: short stories, poetry, the plays—this is all in my Smith chapter.

What’s your process? How does a piece evolve from genesis through the editing stage and on to its debut in the world?

Pretty much every single thing I’ve ever written starts as this quick little snippet, vision, a movie clip of something in my mind. It’s so fast, but packed in that little bit of time. I work around that. This snippet vision isn’t usually of the beginning; more often its somewhere in the middle, and I have to build around it—starting out as a poem and growing into a story and ending up as a play. I’ve been told that’s a lot of steps, but that’s how I write. Though some of these parts have been written in different periods in my life, they’ll link up in my head, and I’ll put all of them together to make something.

I’ve learned to listen to the characters more than to what I want to say. For one of my plays, I had this Q and A with myself, asking myself questions as if I hadn’t written the play. And one of the characters was like, “You wonder where my mother is? I killed that bitch.” As soon as I got to a red light, I called my husband and wrote it into the script.

I live in Baltimore, so I drive back and forth from here to home, and sometimes these little things will happen to me during those drives. If I’m talking to my husband Melvin on the phone, he’ll write down the idea for me since I can’t, or I’ll toss an idea past him.

But as for letting the world see my work, I’ve only just begun to open up. I talked about the fear of getting caught. It’s not about not being good enough—in fact, it’s more like the fear of being good. I want there to be a hell of a payoff, but I don’t want to get a big head. I’ve learned it’s your talents that will get you there, but it’s your character that keeps you. A lot of the stuff I write is very sensitive. The plays, for instance, are going on in November, but my classmates haven’t seen any of them. And it’s mostly been at my professor’s urging over the last three semesters that anyone has seen my work at all.

What’s your current project, now that you’re in your last semester?

I’m working on a longer length play now. Though I’m graduating in J-term, I have the opportunity to have it read in the spring. It’s based on true events, and it will affect certain people. It’s mostly a spoken word play, but it’s called “Unspoken Words: How They See Us,” and it will be about race and gender, classism—playwriting with a mix of poetry. Current students, alums, professors, mentors, friends with different identities have all been contributing. So it’s not just this straight, Christian, black woman writing. I get everybody.

What place does writing have in your life, both now and going forward?

It’s everything. I’m not “trying” to be a writer; I AM a writer. I could talk in completely sentences since two, and I’ve read since three. Put them together, and give me a pen and paper. I’ve been doing it forever. After Smith, it’s possibly two MFAs, in playwriting and poetry. So I will have the credentials.

As I was growing up, there were people who were fascinated by what I wrote. I opened plays with my poetry. Then came the question: where did you study? And I didn’t. This is just me. I realized that to be heard and taken seriously, especially by the people who will open their wallets for organizations and causes I speak for, I’d need an alphabet behind my name. My degree coming from Smith will carry a lot of weight. The idea that I’m fifty years old, my demographics, a black woman of meager means in a white school, white town, and she did this. She not only handled the academics but she handled this social world.

This writer’s goal is to get her voice out. To get other peoples’ voices out. To tell it in a different voice that actually makes people think and want to change. So that they make change. That’s what writing is, for me. People tell me, you can’t make a living off of it, what are you going to do? But I don’t want to make a living, I just don’t want to make a killing. We see peoples’ writing that make others go out and do unseemly things. I don’t want to write something that makes another killing.

I call myself a storyteller, and I just use different mediums to tell the story. And I like hearing the success stories of the everyday person. I said this a couple of times, and people sometimes challenge me on this, but I want to write the success story of the average person. Most people write about the successes of the rich and famous, but I want to write about the person under the bridge. Because it’s a success story at all to survive day after day, under that bridge. I feel a great deal for the underdog. And I never want to get a big head so that I lose touch with that.

Advice for a young writer hoping to get a foothold?

Not everyone is going to respond the same way to your art, but you learn and you grow from that. I’m not about hiding anymore, but I’m also not going to just reveal everything. I have a selective readership. You’ll grow from those disappointments. They’ll make you a better writer. They will. If everybody loves everything you write, you can’t trust that. Guard yourself, guard your secrets, explore, and enjoy.

I need you to know something

I haven’t the tongue to tell you

I think it will be easier this way

My pen has always been kinder, softer

better skilled, doesn’t struggle with a stutter

I think you think

I’m bullshitting you already

that I’m a coward and

easier for whom

Smooth talker

Your platinum-forked tongue always

had the choicest words

could convince a peacock to pluck its feathers

could convince a penguin it could fly

convinced me I was nothing

with and without you

Syllables formed venomous sentences

that snaked and squeezed and strangled my speech

Thanks

You made me a better writer

I want my words to wrap

around your wee willie ass like a widow’s web

spinning, smothering, suffocating

your slick lips in silk

because the shit you do

don’t make up for the shit you’ve done

Shhh

Spend some time

with this something

It’ll make sense

if you shut up long enough

to notice I’m gone